Brief

Architecture of the Urban Commons

Throughout the modern era, since the early 20th century, cities have been variously perceived as,

engines of economic growth “…the locus of productive economic activities and hope for the future” (M A Cohen & K S Lee, World Bank, 1991),

compared to living organisms “…as things which are born and which develop, disintegrate and die.” (J L. Sert, Can Our cities Survive? CIAM 1942),

and even been imagined as utopias composed of standardized systems and uniform patterns that “…would automatically end unemployment and all its evils” (F L. Wright, Broadacre City: A New Community Plan, Architectural Record, 1935).

These perceptions capture some essential aspects of urban life such as the economic opportunities that cities offer, the morphological growth that cities undergo, or the complex spatial patterns that cities embody. They reveal the dynamic nature of urbanism, its intricate textures and incessant evolution, driven by the vibrant variety of activities and people that create, regulate, and perpetuate the city. It is this rich urban diversity within which we situate the “urban commons”, those spaces and buildings within the city that can be shared by all its inhabitants, can accommodate all forms of social interactions, and can exemplify the city’s collective identity.

The architecture that epitomizes this quality has been described as “Urban Artifacts” by Aldo Rossi in his book “The Architecture of the City”. The quality of becoming an identity that not only resides in the minds of the people in the present, but also transcends time to create an unbroken continuity through the history of the city as a definitive descriptor of the physical space itself.

The global urban context today offers numerous examples of such spaces that are open, accessible, and expressive of the city’s public values, through community insight, citizen initiative and collective identity. The designs of these spaces, while highlighting the rich diversity of the people they represent, also uniformly demonstrate the designer’s conscious restraint and sensitivity.

From the Therme Vals in Switzerland, commissioned by the village council of Vals as a hydrotherapy center and built in 1996; to the urban marketplace of Dilli Haat in New Delhi, built in 1994 to empower the craftspeople of rural India; to the Freedom Park in Pretoria, designed in 2006 to commemorate the collective history of the struggle against apartheid; examples of urban commons can be found across the world in every country.

As the world rapidly transforms and witnesses an emergent global urban identity, it is also faced with challenges, both cultural and climatic. The United Nations also recognizes these and has designed the Sustainable Development Goals framework to address the vulnerabilities faced by cities across the world.

Objectives of the competition:

The 11th IDC 2024 invites the participants to analyze the city through this framework and identify an urban space that is potentially accessible to all and can support public functions beyond its intended use. These spaces then become the urban canvas onto which the participants must envision a design intervention that while remaining sensitive to the local context by forming an indelible association with the users, also creates a larger urban identity that would define the shared collective history of the city.

The competition lays strong emphasis on the need for a rigorous analysis of the selected site/area in terms of its accessibility, inclusivity, plurality, multiplicity, and resilience to climate induced vulnerability; as well as on creative design interventions that are citizen driven initiatives that create a collective urban identity.

Eligibility of participants:

The competition is open to architecture students from undergraduate and postgraduate streams as well as recently graduated architects.

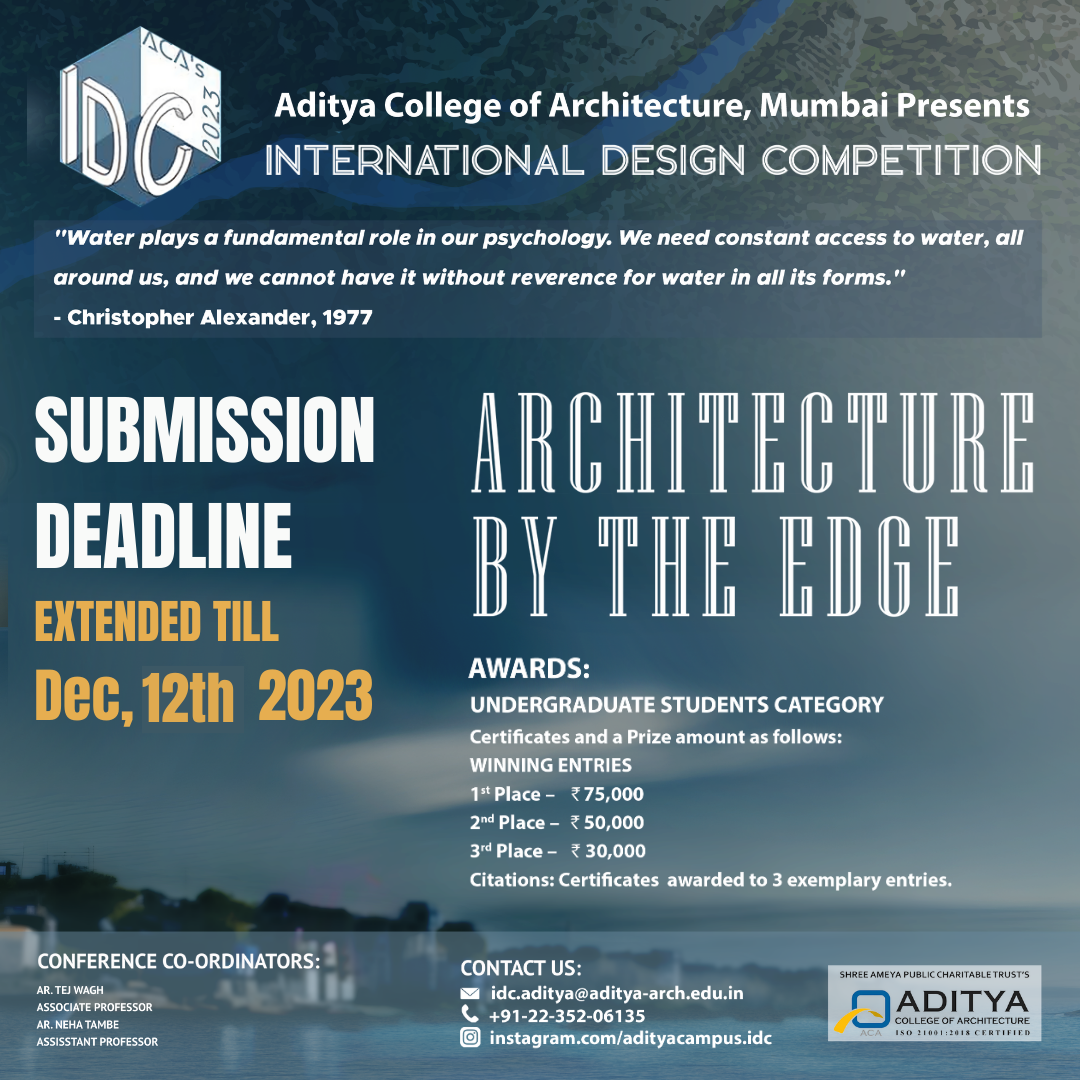

Architecture by the Edge

"Water plays a fundamental role in our psychology. We need constant access to water, all around us, and we cannot have it without reverence for water in all its forms." Christopher Alexander, 1977

Water signifies life and beginning! It is an essential element, providing physical, dimensional, and sensory characteristics to many architectures. Water has the capacity to transform any space with its size, placement, and proportion. With its dimensional quality, it acts as a dynamic axis in every context.

Architecture has, from the beginning, engaged with water, often serving as an aesthetic purpose but more so as a center for human activity. Not only has it served as a transportation network promoting trade and business for centuries, but it has also provided opportunities for recreational activities on an urban scale. Waterfronts have transformed the space into activity hubs. Water, or its presence, can influence the microclimate of a place, creating a comfortable zone, and it holds the capacity to affect and evolve a place at a macro level for any community.

Symbolically, water represents a powerful purifying element; hence, it has been a part of many rituals in most religions. Water is associated with life, death, and rebirth.

However, water is a limited resource and extremely vital to humanity. Our ability to manage water has now become extremely essential to look at using water effectively from an environmental, scientific, artistic, or creative perspective. Extreme events such as climate change, wars, and political upheavals are increasingly susceptible to water-related disasters. Furthermore, the human population explosion has adversely affected water and the various natural habitats of organisms dependent on water.

Water is central to many socio-political conflicts. It is predicted that future wars will be the cause of these very conflicts. It is necessary to break our silence over this cycle of neglect and put the issue of the water crisis under the spotlight. Furthermore, a dialogue around it is needed to adopt more sustainable methods of living.

With this insight, we bring forth the 10th IDC conference with the theme as ‘WATER,’ with the aim to bring into poignant concern water as a perishable resource and the need to bring back sanctity synonymous with the use of water in Architecture.

Water acts as a connector between the physical and the metaphysical. It serves as a reminder of our connection with our ancestors while also serving as a bridge to connect us with the future. Given the current water crisis we find ourselves in, we invite students to produce designs that further this idea of water and its connection with the built environment.

OBJECTIVES OF COMPETITION

- To bring to the forefront the symbiotic relationship we humans share with water

- Bring out qualities of water such as tranquillity, fluidity, sensory and its sense of vastness through design

- Reflecting on how our ancestors shared their relationship with water and how that can be revitalised to suit today’s context

- To keep focus on rising water crisis how can we as architects use water responsibly and wisely

- Leveraging modern technology into constructing with water

- From a historical perspective water always associated with architecture – revitalising water storage facilities and its association with existing urban fabric

- Water and climate change – Coastal degradation

Scope – Area of interest and innovation (any attempt done related to water at any scale) Expected Outcomes based on given requirements Competition Brief

The competition is open to architecture students. Participants are required to study the context chosen by them and propose measures to integrate a selected edge of water as a component and as an integral axis to their proposal. The selected context can be urban, peri-urban, or rural. The design proposal should exhibit an understanding of ecological, social, and cultural characteristics of the place. The proposed design could be part of a built form, landscape to conservation, adaptive reuse, technological or sustainable effort. The participants are encouraged to think on multiple scales.

Eligibility of Participants:

- Undergraduate- B. Arch. students

- Graduate- M. Arch. students

- Recently graduated- B.Arch. students

Building Envelope

Everything we design is a response to the specific climate and culture of a particular place -

A building envelope is the physical separator between the conditioned space and external environment. Building envelops play key role in a structure’s energy efficiency and can account for up to 30% of the primary energy consumption. However, building envelopes are significantly more than this as they act as an integral part of the overall design and contribute to the identity of the structure in the skyline.

Building skins also influence our emotions and behaviour within the enclosed spaces and govern our response to them. They are the language of structural and material expressions for buildings.

Understanding the vital role of building envelopes in overall performance of structures along with its aesthetic and cultural functions, this year IDC intends to design the building envelope and its transformations. The architecture industry has witnessed a huge evolution in the building envelope trends in terms of form, materials, and installation technologies. There has been an ample variation in the traditional and contemporary building envelopes in respect of appearance, aesthetics, and thermal comfort.

The façade of the building is a manifestation of environment controls and technological advances for energy efficiency. Traditional building envelopes that use passive controlling techniques for indoors have governed vernacular architectural forms since millennia. However, in modern times active or semi- active control is achieved in the structures with the range of materials and various technical solutions. It is the result of hundreds of years of optimization to provide a comfortable shelter in a local climate using available materials and known construction methods. For IDC 2022-23 the Participants, need to create a prototype of an architectural envelope for a building typology of their choice in the country of their residence. The structure may be in the urban or rural context but must respond to the climatic as well as socio-cultural environment of the region. the participant must produce his/her own unique design.

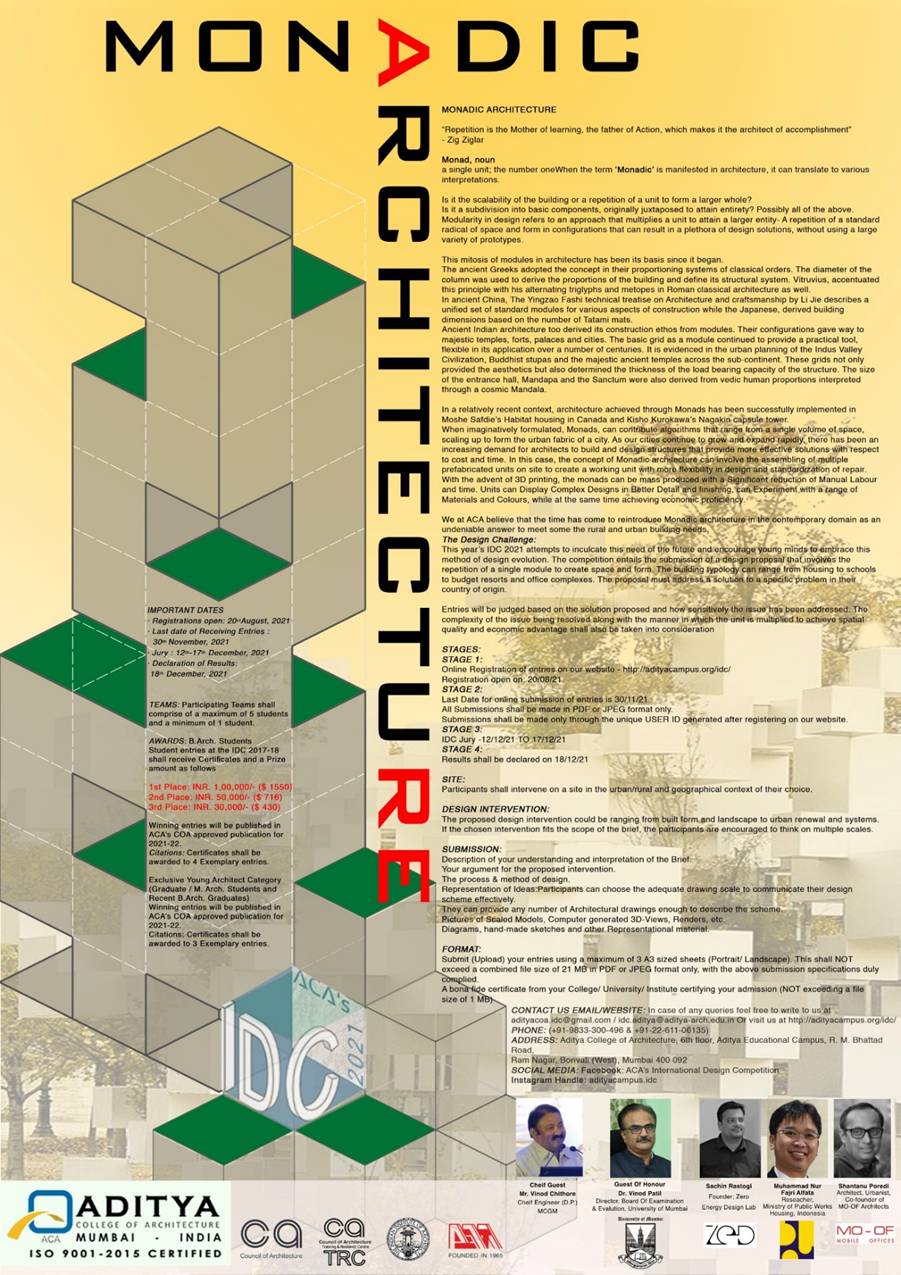

Monadic Architecture

“Repetition is the Mother of learning, the father of Action, which makes it the architect of accomplishment” - Zig Ziglar

Monad, noun

a single unit; the number one.

When the term ‘Monadic’ is manifested in architecture, it can translate to various interpretations.

Is it the scalability of the building or a repetition of a unit to form a larger whole?

Is it a subdivision into basic components, originally juxtaposed to attain entirety? Possibly all of the above. Modularity in design refers to an approach that multiplies a unit to attain a larger entity - A repetition of a standard radical of space and form in configurations that can result in a plethora of design solutions, without using a large variety of prototypes.

This mitosis of modules in architecture has been its basis since it began.

The ancient Greeks adopted the concept in their proportioning systems of classical orders. The diameter of the column was used to derive the proportions of the building and define its structural system. Vitruvius, accentuated this principle with his alternating triglyphs and metopes in Roman classical architecture as well.

In ancient China, The Yingzao Fashi technical treatise on Architecture and craftsmanship by Li Jie describes a unified set of standard modules for various aspects of construction while the Japanese, derived building dimensions based on the number of Tatami mats.

Ancient Indian architecture too derived its construction ethos from modules. Their configurations gave way to majestic temples, forts, palaces and cities. The basic grid as a module continued to provide a practical tool, flexible in its application over a number of centuries. It is evidenced in the urban planning of the Indus Valley Civilization, Buddhist stupas and the majestic ancient temples across the sub-continent. These grids not only provided the aesthetics but also determined the thickness of the load bearing capacity of the structure. The size of the entrance hall, Mandapa and the Sanctum were also derived from vedic human proportions interpreted through a cosmic Mandala.

In a relatively recent context, architecture achieved through Monads has been successfully implemented in Moshe Safdie’s Habitat housing in Canada and Kisho Kurokawa’s Nagakin capsule tower.

When imaginatively formulated, Monads, can contribute algorithms that range from a single volume of space, scaling up to form the urban fabric of a city. As our cities continue to grow and expand rapidly, there has been an increasing demand for architects to build and design structures that provide more effective solutions with respect to cost and time. In this case, the concept of Monadic architecture can involve the assembling of multiple prefabricated units on site to create a working unit with more flexibility in design and standardization of repair.

With the advent of 3D printing, the monads can be mass produced with a Significant reduction of Manual Labour and time. Units can Display Complex Designs in Better Detail and finishing, can Experiment with a range of Materials and Colours, while at the same time achieving economic proficiency.

We at ACA believe that the time has come to reintroduce Monadic architecture in the contemporary domain as an undeniable answer to meet some the rural and urban building needs

The Design Challenge:

This year’s IDC 2021 attempts to inculcate this need of the future and encourage young minds to embrace this method of design evolution. The competition entails the submission of a design proposal that involves the repetition of a single module to create space and form. The building typology can range from housing to schools to budget resorts and office complexes. The proposal must address a solution to a specific problem in their country of origin.

Entries will be judged based on the solution proposed and how sensitively the issue has been addressed. The complexity of the issue being resolved along with the manner in which the unit is multiplied to achieve spatial quality and economic advantage shall also be taken into consideration

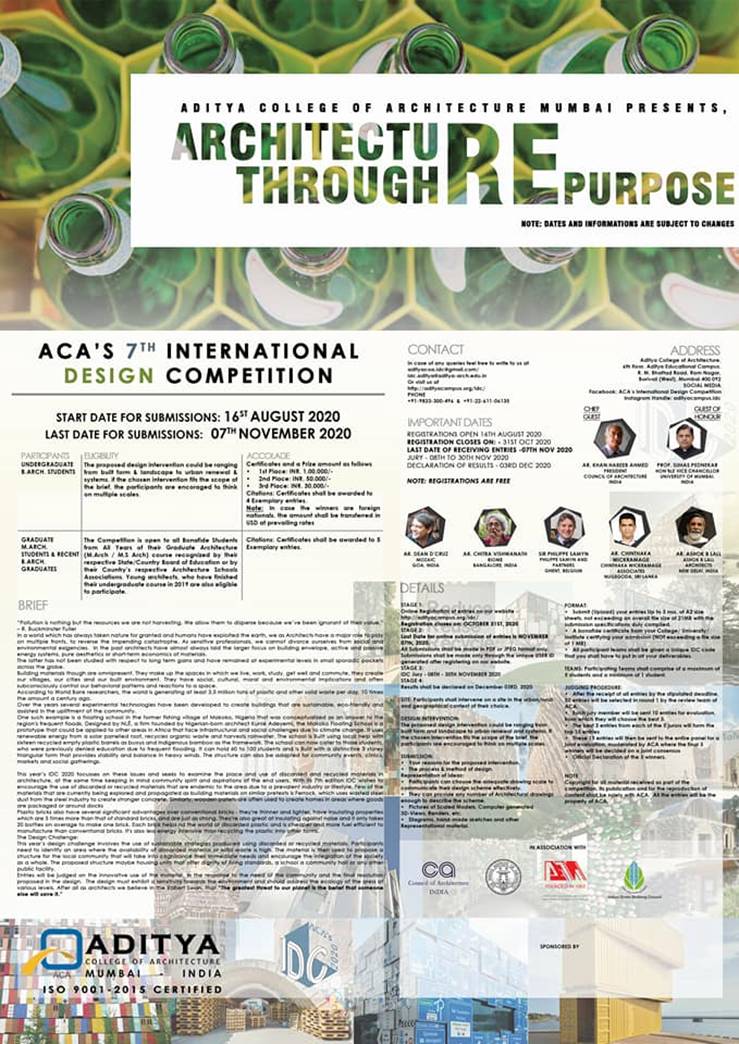

Architecture Through RePurpose

The first purpose of architecture is to create habitat that fulfil the needs of society or individuals for places to work and live. It is a manifestation and expression of cultural values of the society with which it interacts. Over the years Architectural Design and perception have changed dramatically, transcending through the passage of time, absorbing and reflecting the changing trends in human behaviour brought about by technological advances and modernization. The entire spectrum from space to urban planning needs to follow a direction that amalgamates tradition and technology capturing the psyche of the society.

Mainstream Urban architecture has inherently remained universal or generic enough to be easily replicated anywhere else in the world thereby losing its connect with the local context. Whereas, the 2018’s Pritzker Prize winner B. V. Doshi’s Aranya Township Project (1983) in Indore, Central India which was a low-income incentivised site and services vernacular housing project. It is an ideal example for understanding the concept of designing for community inclusiveness and proposing vernacular architecture as a medium while dealing with modern day complexities of high-density urbanisation.

The round building housing complex designed by Urbanus architects in Guangzhou is inspired by ancient ‘Tulou’ that has encouraged community living in China over centuries. The traditional Tulou dwelling is a rural Chinese housing typology originating in the 12th Century, particularly to the Hakka mountains. Following the Chinese dwelling tradition of ‘closed outside, open inside’, the self-contained structures formed a small walled city, each housing up to 800 people. The Fortified walls built contained the individual dwellings, enclosing a generous inner-courtyard and communal facilities. The homes themselves were small and modest but shared amenity spaces including ceremonial halls, water-wells, bathrooms and washrooms. This Aga Khan winning project involved the design of a 220-apartment housing complex for low income families. The urban Tulou consists of an outer circular block with a rectangular box within that is connected to the outer ring by bridges and a courtyard. Both the circular and rectangular blocks contain small apartment units; the spaces in between are for circulation and community use. The lower floors contain shops and other community facilities.

How do we continue to evolve as a society without neglecting our past? What are the ways by which architecture can take on the present-day challenges posing as a global driver of change and simultaneously engaging with the local culture? Perhaps if one discovers as of ‘why’ inheritance matters while looking forward in time, the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of responsive design will reveal itself.

The Design Challenge

ACA’s 6th International Design Competition wishes to investigate the various possible outcomes through which inheritance can perform as a catalyst while creating a design that respects both past and present. Moreover, the competition puts forth the question on how to identify our inheritance and where do we start looking for it in the ocean of tangible and intangible heritage which is futuristic yet sustainable. When it comes to engaging with contemporary architecture, how can we adopt contextual parameters of culture, socio economic values, political and ethical understanding of Inheritance.

The competition invites students of the architectural fraternity to evolve a design that successfully bridges these gaps in an urban precinct that integrates the community and encourages sustainable expression through built form. After all as Frank Lloyd Wright, once put it,

“Architecture is life, or at least it is life itself taking form and therefore it is the truest record of life as it was lived in the world yesterday, as it is lived today or ever will be lived.

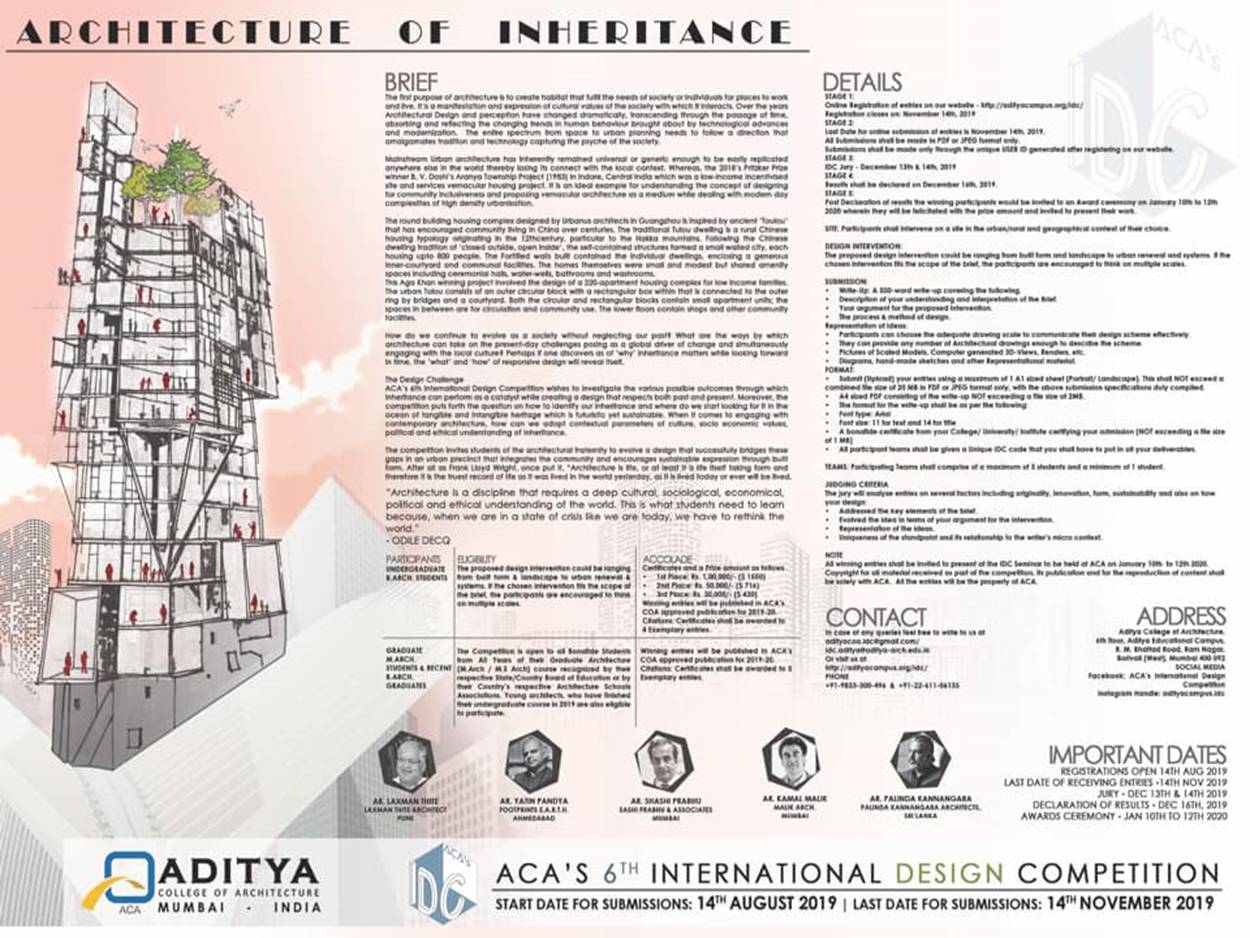

Architecture of Inheritance

The first purpose of actecture to create hotter that tut the needs of society or individus for places to work and ve. It|s a manteigton and expreson of cultural values of the society with which teracts Over The pers Architectural Design and perception have charged dramaticaly, Ironscending through the page of absoning and facting the changing hands in human behaviour brought about by technological advances and modernization The entire spectrum bom space to urban planning needs to folow a direction that amalgamates on and technology capturing the payche of the society

Mambon achfecture has inherently remained univeral or genert enough to be early replicated the wond thereby long its connect with the local contest. Whereas the 2018|s Poker Pro Dost|s Aronya Township Project 195 in Indore, Centra india which was a low-income incentived she and services venacular housing project on ideat example for undenhanding the concept of designing for community inclusiveness and proposing veg The round building housing complex designed by Urbanus architects in Guangehou is ined by ancient" that has encouraged community ving in China over centuries, the bodional fut deeling a rural Chine housing typogy gang the 12mcentury, partcutar to the Hamounts, fotosing the Chr housing upto 800 people. The Forted wals but contained the individual dwellings, enclosing a gene leer-courtyard and communal faces. The homes themselves were smal and modest but shored amenity spaces including ceremont hat wowels, bathrooms and washrooms

The Aga Khan wing project hoved the design of a 220-apartment housing complex for low income fam the urban Tutu costs of on outer ccur block with a rectangular box within that is connected to the outer ring by bridges and a courtyard. Both the crouler and rectangular blocks contain anal apartment unhc the spaces in between are for cute and community use. The lower toons contain shops and other community How do we continue to evolve as a sciety with neglecting our pout what are the way by which architecture can take on the present-day challenges posing a global diver of change and simultaneously engaging with the loco cuturet Pertaps one covers us of why inhertance matters we looking forward In the |what and how of responsive design will revet het

The Design Challenge

ACA|S intematonal Design Competto wishes to investigate the various peuble outcomes through which whehance can perform as a cast while creating a design that respect bo pad and present. Moreover, the compatton puts forth the question un how to identify our hence and where do we start looking for in the ocean of large and tangible heage which is fututo yet anginate When it comes to engaging with potical and whical understanding of whence

The competton Intes students of the architecturety to save i den that succulty bridges the gaps in an urban precinct mat integrates the community and encourages are expression through butt Alter at a fron Loyd Wright, once put . "Achfecture iste, or of the the form and uest record of ife wed in the world yesday, dodav "Architecture is a discipline that requires a deep cultural sociological, economical political and ethical undentanding of the world. This is what students need to leam because, when we are in a state of crisis like we are today, we have to rethink the world.

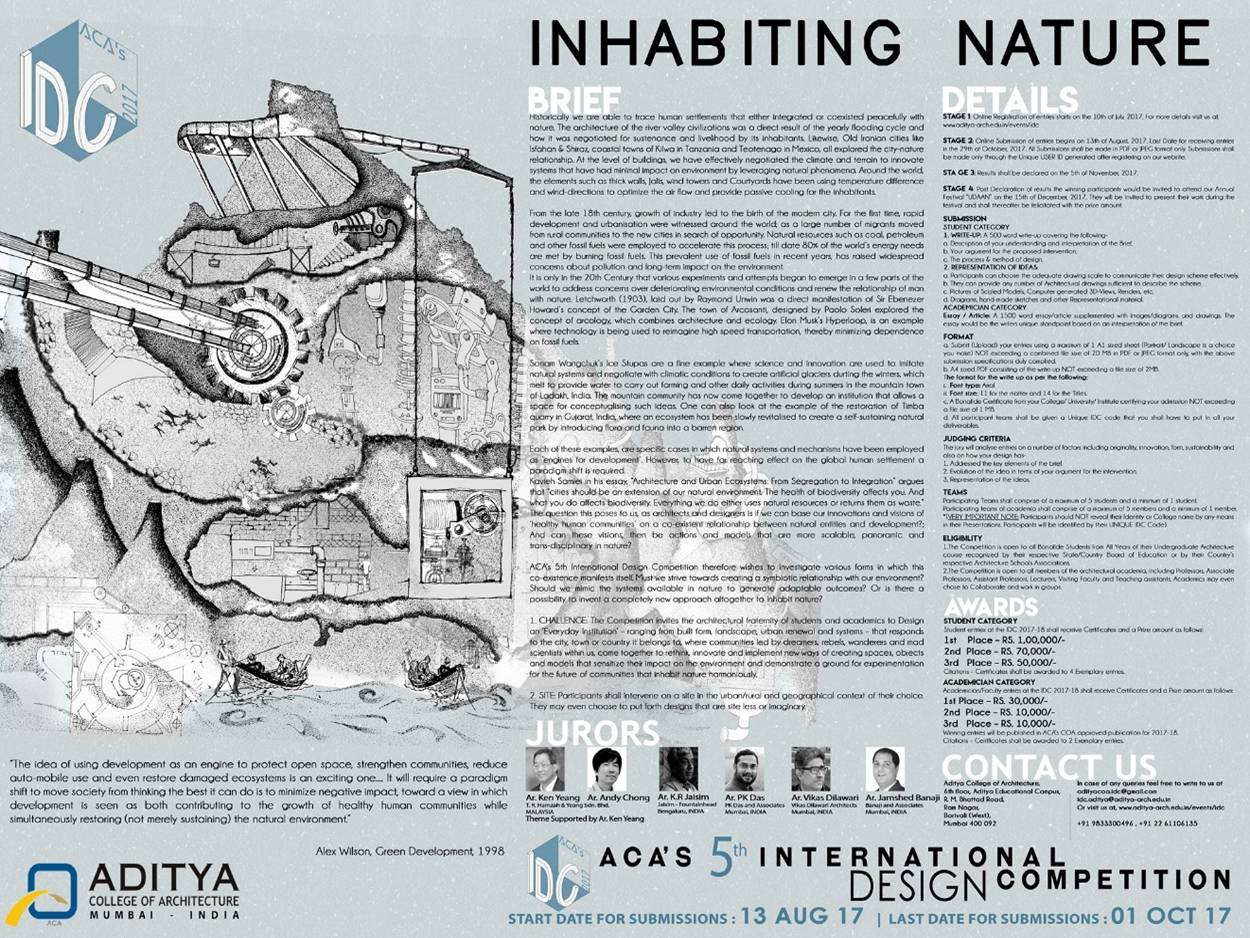

Inhabiting Nature

"The idea of using development as an engine to protect open space, strengthen communities, reduce auto-mobile use and even restore damaged ecosystems is an exciting one.... It will require a paradigm shift to move society |from thinking the best it can do is to minimize negative impact, toward a view in which development is seen as both contributing to the growth of healthy human communities while simultaneously restoring (not merely sustaining) the natural environment. |"

- Alex Wilson, Green Development, 1998

Historically we are able to trace human settlements that either integrated or coexisted peacefully with nature. The architecture of the river valley civilizations was a direct result of the yearly flooding cycle and how it was negotiated for sustenance and livelihood by its inhabitants. Likewise, Old Iranian cities like Isfahan & Shiraz, coastal towns of Kilwa in Tanzania and Teotenago in Mexico, all explored the city-nature relationship. At the level of buildings, we have effectively negotiated the climate and terrain to innovate systems that have had minimal impact on environment by leveraging natural phenomena. Around the world, the elements such as thick walls, Jalis, wind towers and Courtyards have been using temperature difference and wind-directions to optimize the air flow and provide passive cooling for the inhabitants.

From the late 18th century, growth of industry led to the birth of the modern city. For the first time, rapid development and urbanisation were witnessed around the world; as a large number of migrants moved from rural communities to the new cities in search of opportunity. Natural resources such as coal, petroleum and other fossil fuels were employed to accelerate this process; till date 80% of the world’s energy needs are met by burning fossil fuels. This prevalent use of fossil fuels in recent years, has raised widespread concerns about pollution and long-term impact on the environment.

It is only in the 20th Century that various experiments and attempts began to emerge in a few parts of the world to address concerns over deteriorating environmental conditions and renew the relationship of man with nature. Letchworth (1903), laid out by Raymond Unwin was a direct manifestation of Sir Ebenezer Howard’s concept of the Garden City. The town of Arcosanti, designed by Paolo Soleri explored the concept of arcology, which combines architecture and ecology. Elon Musk’s Hyperloop, is an example where technology is being used to reimagine high speed transportation, thereby minimizing dependence on fossil fuels.

Sonam Wangchuk’s Ice Stupas are a fine example where science and innovation are used to imitate natural systems and negotiate with climatic conditions to create artificial glaciers during the winters, which melt to provide water to carry out farming and other daily activities during summers in the mountain town of Ladakh, India. The mountain community has now come together to develop an institution that allows a space for conceptualising such ideas. One can also look at the example of the restoration of Timba quarry in Gujarat, India, where an ecosystem has been slowly revitalised to create a self-sustaining natural park by introducing flora and fauna into a barren region.

Each of these examples, are specific cases in which natural systems and mechanisms have been employed as ‘engines for development’. However, to have far reaching effect on the global human settlement a paradigm shift is required.

Kavieh Samiei in his essay, “Architecture and Urban Ecosystems: From Segregation to Integration” argues that “cities should be an extension of our natural environment. The health of biodiversity affects you. And what you do affects biodiversity. Everything we do either uses natural resources or returns them as waste.” The question this poses to us, as architects and designers is if we can base our innovations and visions of ‘healthy human communities’ on a co-existent relationship between natural entities and development?; And can these visions, then be actions and models that are more scalable, panoramic and trans-disciplinary in nature?

ACA’s 5th International Design Competition therefore wishes to investigate various forms in which this co-existence manifests itself. Must we strive towards creating a symbiotic relationship with our environment? Should we mimic the systems available in nature to generate adaptable outcomes? Or is there a possibility to invent a completely new approach altogether to inhabit nature?

The Competition invites the architectural fraternity of students and academics to Design an ‘Everyday Institution’ – ranging from built form and landscape to urban renewal and systems - that responds to the city, town or country it belongs to, where communities led by dreamers, rebels, wanderers and mad scientists within us, come together to rethink, innovate and implement new ways of creating spaces and demonstrate a ground for experimentation for the future of communities that inhabit nature harmoniously.

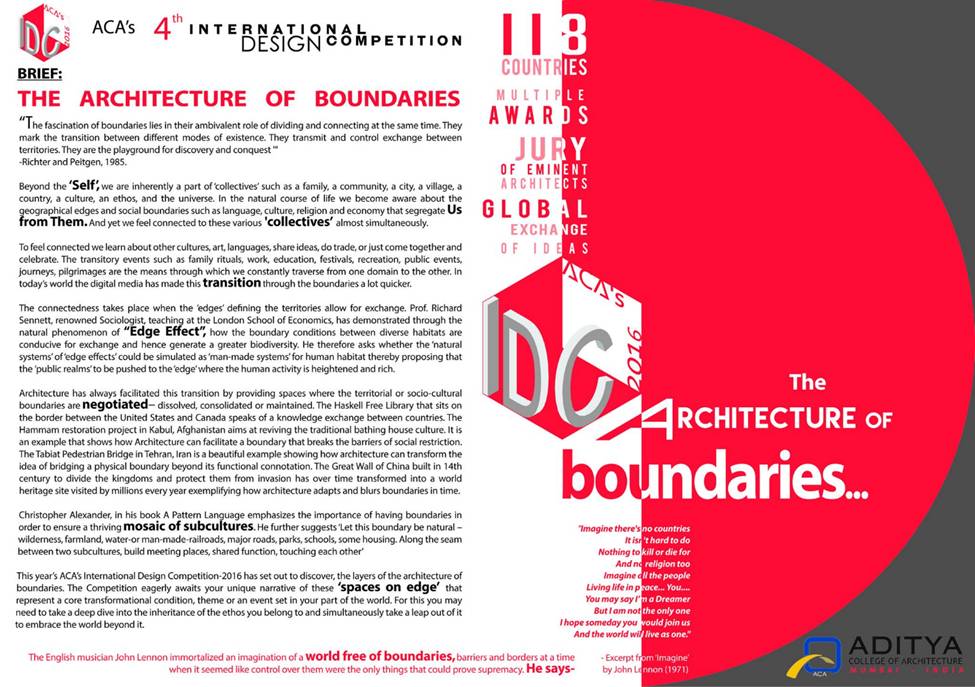

The Architecture of Boundaries

THE ARCHITECTURE OF BOUNDARIES "The fascination of boundaries lies in their ambivalent role of dividing and connecting at the same time. They mark the transition between different modes of existence. They transmit and control exchange between territories. They are the playground for discovery and conquest""

-Richter and Peitgen, 1985.

Beyond the |Self, we are inherently a part of |collectives| such as a family, a community, a city, a village, a country, a culture, an ethos, and the universe. In the natural course of life we become aware about the geographical edges and social boundaries such as language, culture, religion and economy that segregate from Them. And yet we feel connected to these various |collectives| almost simultaneously.

To feel connected we learn about other cultures, art, languages, share ideas, do trade, or just come together and celebrate. Transitory events such as family rituals, work, education, festivals, recreation, public events, journeys, pilgrimages are the means through which we constantly traverse from one domain to the other. In today|s world the digital media has made this transition through the boundaries a lot quicker.

The connectedness takes place when the |edges| defining the territories allow for exchange. Prof. Richard Sennett, renowned Sociologist, teaching at the London School of Economics, has demonstrated through the natural phenomenon of "Edge Effect", how the boundary conditions between diverse habitats are conducive for exchange and hence generate a greater biodiversity. He therefore asks whether the |natural systems| of |edge effects| could be simulated as |man-made systems| for human habitat thereby proposing that the |public realms| to be pushed to the |edge| where the human activity is heightened and rich.

Architecture has always facilitated this transition by providing spaces where the territorial or socio-cultural boundaries are negotiated- dissolved, consolidated or maintained. The Haskell Free Library that sits on the border between the United States and Canada speaks of a knowledge exchange between countries. The Hammam restoration project in Kabul, Afghanistan aims at reviving the traditional bathing house culture. It is an example that shows how Architecture can facilitate a boundary that breaks the barriers of social restriction. The Tabiat Pedestrian Bridge in Tehran, Iran is a beautiful example showing how architecture can transform the idea of bridging a physical boundary beyond its functional connotation. The Great Wall of China built in 14th century to divide the kingdoms and protect them from invasion has over time transformed into a world heritage site visited by millions every year exemplifying how architecture adapts and blurs boundaries in time.

Christopher Alexander, in his book A Pattern Language emphasizes the importance of having boundaries in order to ensure a thriving mosaic of subcultures. He further suggests |Let this boundary be natural- wilderness, farmland, water-or man-made-railroads, major roads, parks, schools, some housing. Along the seam between two subcultures, build meeting places, shared function, touching each other|

This year|s ACA|s International Design Competition-2016 has set out to discover, the layers of the architecture of boundaries. The Competition eagerly awaits your unique narrative of these |spaces on edge| that represent a core transformational condition, theme or an event set in your part of the world. For this you may need to take a deep dive into the inheritance of the ethos you belong to and simultaneously take a leap out of it to embrace the world beyond it.